Mixed martial arts

This article may be too long to read and navigate comfortably. (February 2022) |

| |

| Highest governing body | International Mixed Martial Arts Federation |

|---|---|

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full contact |

| Mixed-sex | No, separate male and female events |

| Type | Combat sport |

| Venue | Octagonal cage, other type of cage, MMA ring |

Mixed martial arts (MMA)[a] is a full-contact fighting sport based on striking and grappling, incorporating techniques from various combat sports from around the world.[10]

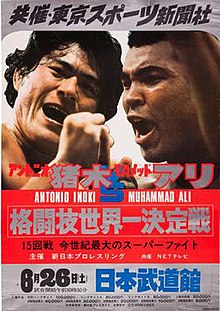

In the early 20th century, various inter-stylistic contests took place throughout Japan and the countries of East Asia. At the same time, in Brazil there was a phenomenon called vale tudo, which became known for unrestricted fights between various styles such as judo, Brazilian jiu-jitsu, catch wrestling, luta livre, Muay Thai and capoeira. An early high-profile mixed bout was Kimura vs. Gracie in 1951. In mid-20th century Hong Kong, rooftop street fighting contests between different martial arts styles gave rise to Bruce Lee's hybrid martial arts style Jeet Kune Do. Another precursor to modern MMA was the 1976 Ali vs. Inoki exhibition bout, fought between boxer Muhammad Ali and wrestler Antonio Inoki in Japan, where it later inspired the foundation of Shooto in 1985, Pancrase in 1993, and the Pride Fighting Championships in 1997.

In the 1990s, the Gracie family brought their Brazilian jiu-jitsu style, first developed in Brazil from the 1920s, to the United States—which culminated in the founding of the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC) promotion company in 1993. The company held an event with almost no rules, mostly due to the influence of Art Davie and Rorion Gracie attempting to replicate mixed contests that existed in Brazil[11] and Japan. They would later implement a different set of rules (example: eliminating kicking a grounded opponent), which differed from other leagues which were more in favour of realistic, "street-like" fights.[12] The first documented use of the term mixed martial arts was in a review of UFC 1 by television critic Howard Rosenberg in 1993.

Originally promoted as a competition to find the most effective martial arts for real unarmed combat, competitors from different fighting styles were pitted against one another in contests with relatively few rules.[13] Later, individual fighters incorporated multiple martial arts into their style. MMA promoters were pressured to adopt additional rules to increase competitors' safety, to comply with sport regulations and to broaden mainstream acceptance of the sport.[14] Following these changes, the sport has seen increased popularity with a pay-per-view business that rivals boxing and professional wrestling.[15]

History

[edit]Antiquity

[edit]

In ancient China, combat sport appeared in the form of Leitai, a no-holds-barred mixed combat sport that combined Chinese martial arts, boxing and wrestling.[16]

In ancient Greece, there was a sport called pankration, which featured grappling and striking skills similar to those found in modern MMA. Pankration was formed by combining the already established wrestling and boxing traditions and, in Olympic terms, first featured in the 33rd Olympiad in 648 BC. All strikes and holds were allowed with the exception of biting and gouging, which were banned. The fighters, called pankratiasts, fought until someone could not continue or signaled submission by raising their index finger; there were no rounds.[18][19] According to the historian E. Norman Gardiner, "No branch of athletics was more popular than the pankration."[20] There is also evidence of similar mixed combat sports in ancient Egypt, India and Japan.[16]

Modern-era precursors

[edit]The mid-19th century saw the prominence of the new sport savate in the combat sports circle. French savate fighters wanted to test their techniques against the traditional combat styles of its time. In 1852, a contest was held in France between French savateurs and English bare-knuckle boxers in which French fighter Rambaud alias la Resistance fought English fighter Dickinson and won using his kicks. However, the English team still won the four other match-ups during the contest.[21] Contests occurred in the late 19th to mid-20th century between French savateurs and other combat styles. Examples include a 1905 fight between French savateur George Dubois and a judo practitioner Re-nierand which resulted in the latter winning by submission, as well as the highly publicized 1957 fight between French savateur and professional boxer Jacques Cayron and a young Japanese karateka named Mochizuki Hiroo which ended when Cayron knocked Hiroo out with a hook.[21]

Catch wrestling appeared in the late 19th century, combining several global styles of wrestling, including Indian pehlwani and English wrestling.[22][23] In turn, catch wrestling went on to greatly influence modern MMA.[citation needed][24] No-holds-barred fighting reportedly took place in the late 1880s when wrestlers representing the style of catch wrestling and many others met in tournaments and music-hall challenge matches throughout Europe. In the US, the first major encounter between a boxer and a wrestler in modern times took place in 1887 when John L. Sullivan, then heavyweight world boxing champion, entered the ring with his trainer, wrestling champion William Muldoon, and was slammed to the mat in two minutes. The next publicized encounter occurred in the late 1890s when future heavyweight boxing champion Bob Fitzsimmons took on European wrestling champion Ernest Roeber. In September 1901, Frank "Paddy" Slavin, who had been a contender for Sullivan's boxing title, knocked out future world wrestling champion Frank Gotch in Dawson City, Canada.[25] The judo-practitioner Ren-nierand, who gained fame after defeating George Dubois, would fight again in another similar contest, which he lost to Ukrainian Catch wrestler Ivan Poddubny.[21]

Another early example of mixed martial arts was Bartitsu, which Edward William Barton-Wright founded in London in 1899. Combining catch wrestling, judo, boxing, savate, jujutsu and canne de combat (French stick fighting), Bartitsu was the first martial art known to have combined Asian and European fighting styles,[26] and which saw MMA-style contests throughout England, pitting European catch wrestlers and Japanese judoka champions against representatives of various European wrestling styles.[26]

Among the precursors of modern MMA are mixed style contests throughout Europe, Japan, and the Pacific Rim during the early 1900s.[27] In Japan, these contests were known as merikan, from the Japanese slang for "American [fighting]". Merikan contests were fought under a variety of rules, including points decision, best of three throws or knockdowns, and victory via knockout or submission.[28]

Sambo, a martial art and combat sport developed in Russia in the early 1920s, merged various forms of combat styles such as wrestling, judo and striking into one unique martial art.[29][30] The popularity of professional wrestling, which was contested under various catch wrestling rules at the time, waned after World War I, when the sport split into two genres: "shoot", in which the fighters actually competed, and "show", which evolved into modern professional wrestling.[31] In 1936, heavyweight boxing contender Kingfish Levinsky and professional wrestler Ray Steele competed in a mixed match, which catch wrestler Steele won in 35 seconds.[31] 27 years later, Ray Steele's protégé Lou Thesz fought boxer Jersey Joe Walcott twice in mixed style bouts. The first match was a real contest which Thesz won while the second match was a work, which Thesz also won.

In the 1940s in the Palama Settlement in Hawaii, five martial arts masters, under the leadership of Adriano Emperado, curious to determine which martial art was best, began testing each other in their respective arts of kenpo, jujitsu, Chinese and American boxing and tang soo do. From this they developed kajukenbo, the first American mixed martial arts.

In 1951, a high-profile grappling match was Masahiko Kimura vs. Hélio Gracie, which was wrestled between judoka Masahiko Kimura and Brazilian jiu jitsu founder Hélio Gracie in Brazil. Kimura defeated Gracie using a gyaku-ude-garami armlock, which later became known as the "Kimura" in Brazilian jiu jitsu.[32] In 1963, a catch wrestler and judoka "Judo" Gene Lebell fought professional boxer Milo Savage in a no-holds-barred match. Lebell won by Harai Goshi to rear naked choke, leaving Savage unconscious. This was the first televised bout of mixed-style fighting in North America. The hometown crowd was so enraged that they began to boo and throw chairs at Lebell.[33]

On February 12, 1963, three karatekas from Oyama dojo (kyokushin later) went to the Lumpinee Boxing Stadium in Thailand and fought against three Muay Thai fighters. The three kyokushin karate fighters were Tadashi Nakamura, Kenji Kurosaki and AkiFujihira (also known as Noboru Osawa), while the Muay Thai team of three authentic Thai fighter.[34] Japan won 2–1: Tadashi Nakamura and Akio Fujihira both knocked out their opponents with punches while Kenji Kurosaki, who fought the Thai, was knocked out by elbows. The Japanese fighter who lost, Kenji Kurosaki, was a kyokushin instructor, rather than a contender, and that he had stood in as a substitute for the absent chosen fighter. In June of the same year, karateka and future kickboxer Tadashi Sawamura faced top Thai fighter Samarn Sor Adisorn: Sawamura was knocked down sixteen times on his way to defeat.[34] Sawamura went on to incorporate what he learned in that fight in kickboxing tournaments.

During the late 1960s to early 1970s, the concept of hybrid martial arts was popularized in the West by Bruce Lee via his system of Jeet Kune Do.[35] Lee believed that "the best fighter is not a boxer, karate or judo man. The best fighter is someone who can adapt to any style, to be formless, to adopt an individual's own style and not following the system of styles."[36] In 2004, UFC President Dana White would call Lee the "father of mixed martial arts" stating: "If you look at the way Bruce Lee trained, the way he fought, and many of the things he wrote, he said the perfect style was no style. You take a little something from everything. You take the good things from every different discipline, use what works, and you throw the rest away".[37]

A contemporary of Bruce Lee, Wing Chun practitioner Wong Shun Leung, gained prominence fighting in 60–100 illegal beimo fights against other Chinese martial artists of various styles. Wong also fought and won against Western fighters of other combat styles, such as his match against Russian boxer Giko,[38] his televised fight against a fencer,[39] and his fight against Taiwanese kung fu master Wu Ming Jeet.[40] Wong combined boxing and kickboxing into his kung fu, as Bruce Lee did.

Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki took place in Japan in 1976. The classic match-up between professional boxer and professional wrestler turned sour as each fighter refused to engage in the other's style, and after a 15-round stalemate it was declared a draw. Muhammad Ali sustained a substantial amount of damage to his legs, as Antonio Inoki slide-kicked him continuously for the duration of the bout, causing him to be hospitalized for the next three days.[41] The fight played an important role in the history of mixed martial arts.[42]

The basis of modern mixed martial arts in Japan can be found across several shoot-style professional wrestling promotions such as UWF International and Pro Wrestling Fujiwara Gumi, both founded in 1991, that attempted to create a combat-based style which blended wrestling, kickboxing and submission grappling. Another promotion formed around the same time by Akira Maeda called Fighting Network RINGS initially started as a shoot-style professional wrestling promotion but it also promoted early mixed martial arts contests. From 1995 onwards it began identifying itself as a mixed martial arts promotion and moved away from the original shoot style. Professional wrestlers Masakatsu Funaki and Minoru Suzuki founded Pancrase in 1993 which promoted legitimate contests initially under professional wrestling rules. These promotions inspired Pride Fighting Championships which started in 1997. Pride was acquired by its rival Ultimate Fighting Championship in 2007.[43][44]

A fight between Golden Gloves boxing champion Joey Hadley and Arkansas Karate Champion David Valovich happened on June 22, 1976, at Memphis Blues Baseball Park. The bout had mixed rules: the karateka was allowed to use his fists, feet and knees, while the boxer could only use his fists. Hadley won the fight via knockout on the first round.[45]

In 1988, Rick Roufus challenged Changpuek Kiatsongrit to a non-title Muay Thai vs. kickboxing super fight. Roufus was at the time an undefeated Kickboxer and held both the KICK Super Middleweight World title and the PKC Middleweight U.S. title. Kiatsongrit was finding it increasingly difficult to get fights in Thailand as his weight (70 kg) was not typical for Thailand, where competitive bouts tended to be at the lower weights. Roufus knocked Changpuek down twice with punches in the first round, breaking Changpuek's jaw, but lost by technical knockout in the fourth round due to the culmination of low kicks to the legs that he was unprepared for. This match was the first popular fight which showcased the power of such low kicks to a predominantly Western audience.[46]

Growth of MMA

[edit]The growth of Mixed Martial Arts (MMA) globally has been remarkable over the past few decades. MMA has evolved from being a niche combat sport to one of the most popular and commercially successful sports worldwide.[47]

Timeline of major events

[edit]| 2,000+ years ago | – Leitai | |

| – Pankration | ||

| Late 19th century | – Hybrid martial arts | |

| – Catch wrestling | ||

| Late 1880s | – Early mixed style matches | |

| 1899 | – Barton-Wright and Bartitsu | |

| Early 1900s | – Merikan contests | |

| 1920s | – Early vale tudo competitions and Gracie Challenge matches | |

| 1950s–1960s | – Hong Kong rooftop street fights | |

| 1963 | – Gene Lebell vs. Milo Savage | |

| 1960s–1970s | – Bruce Lee and Jeet Kune Do | |

| 1970s | – Antonio Inoki and Ishu Kakutōgi Sen | |

| 1974 | – Kickboxing "Full Contact Karate" (a hybrid Martial Art encompassing Boxing, Karate, Taekwondo and other styles) rises to prominence in the United States with the first Professional Karate Association world championships. | |

| 1976 | – Muhammad Ali vs. Antonio Inoki | |

| 1979–1980 | – First MMA promotion in the U.S. forms – CV Productions, Inc.'s Tough Guy Contest | |

| 1983 | – First bill introduced to outlaw MMA in the U.S. – The Tough Guy Law | |

| 1985 | – First MMA promotion in Japan forms – Shooto | |

| 1989 | – First professional Shooto event held | |

| 1991 | – First Desafio (BJJ vs. Luta Livre) event | |

| 1993 | – Pancrase forms | |

| – UFC forms | ||

| 1995 | – The L-1 Tournament, the first all-women's MMA event, was held by LLPW | |

| Mid/Late 1990s | – International vale tudo competitions | |

| 1997–2007 | – PRIDE FC era | |

| 1997 | – First MMA promotion in Russia forms – M-1 Global | |

| 1999 | – International Sport Combat Federation founded as the first sanctioning body of MMA | |

| 2000 | – New Jersey SACB develops the Unified Rules of MMA | |

| 2001 | – Zuffa buys UFC | |

| – First MMA promotion in the UK forms – Cage Warriors | ||

| 2005 | – The Ultimate Fighter debuts | |

| – US Army begins sanctioning MMA | ||

| 2006 | – Zuffa buys WFA and WEC | |

| – UFC 66 generates over a million PPV buys | ||

| 2007 | – Zuffa buys PRIDE FC | |

| 2008 | – EliteXC: Primetime gains 6.5 million peak viewers on CBS | |

| 2009 | – MMA promotion in Mexico forms – Ultimate Warrior Challenge Mexico | |

| – Strikeforce holds the first major MMA card with a female main event | ||

| 2011 | – ONE FC forms | |

| – WEC merged with UFC | ||

| – Zuffa buys Strikeforce | ||

| – Velasquez vs. Dos Santos gains 8.8 million peak viewers on Fox | ||

| 2012 | – International Mixed Martial Arts Federation was founded with support from UFC | |

| 2013 | – UFC 157: Rousey vs. Carmouche is headlined by the first women's bout in UFC history | |

| 2016 | – WME-IMG buys UFC for US$4 billion | |

| 2017 | – The currently most important promotion in Mexico and Latin America is formed - LUX Fight League | |

| – WME-IMG changed its holding name to Endeavor | ||

| 2023 | – UFC merged with WWE, with both continuing to run as separate divisions of TKO Group Holdings | |

| – PFL buys Bellator MMA |

Modern sport

[edit]

The movement that led to the creation of present-day mixed martial arts scenes emerged from a confluence of several earlier martial arts scenes: the vale tudo events in Brazil, rooftop fights in Hong Kong's street fighting culture, and professional wrestlers, especially in Japan.

Vale tudo began in the 1920s and became renowned through its association with the "Gracie challenge", which was issued by Carlos Gracie and Hélio Gracie and upheld later by descendants of the Gracie family. The "Gracie Challenges" were held in the garages and gyms of the Gracie family members. When the popularity grew, these types of mixed bouts were a staple attraction at the carnivals in Brazil.[48]

In the mid-20th century, mixed martial arts contests emerged in Hong Kong's street fighting culture in the form of rooftop fights. During the early 20th century, there was an influx of migrants from mainland China, including Chinese martial arts teachers who opened up martial arts schools in Hong Kong. In the mid-20th century, soaring crime in Hong Kong, combined with limited Hong Kong Police manpower, led to many young Hongkongers learning martial arts for self-defence. Around the 1960s, there were about 400 martial arts schools in Hong Kong, teaching their own distinctive styles of martial arts. In Hong Kong's street fighting culture, there emerged a rooftop fight scene in the 1950s and 1960s, where gangs from rival martial arts schools challenged each other to bare-knuckle fights on Hong Kong's rooftops, in order to avoid crackdowns by colonial British Hong Kong authorities. The most famous fighter to emerge from Hong Kong's rooftop fight scene was Bruce Lee, who combined different techniques from different martial arts schools into his own hybrid martial arts system called Jeet Kune Do. Lee went on to popularize the concept of mixed martial arts internationally.[49]

Early mixed-match martial arts professional wrestling bouts in Japan (known as Ishu Kakutōgi Sen (異種格闘技戦), literally "heterogeneous combat sports bouts") became popular with Antonio Inoki only in the 1970s. Inoki was a disciple of Rikidōzan, but also of Karl Gotch, who trained numerous Japanese wrestlers in catch wrestling.

Regulated mixed martial arts competitions were first introduced in the United States by CV Productions, Inc. Its first competition, called Tough Guy Contest was held on March 20, 1980, New Kensington, Pennsylvania, Holiday Inn. During that year the company renamed the brand to Super Fighters and sanctioned ten regulated tournaments in Pennsylvania. In 1983, Pennsylvania State Senate passed a bill known as the "Tough Guy Law" that specifically called for: "Prohibiting Tough Guy contests or Battle of the Brawlers contests", and ended the sport.[50][51][52]

Japan had its own form of mixed martial arts discipline, Shooto, which evolved from shoot wrestling in 1985, as well as the shoot wrestling derivative Pancrase, which was founded as a promotion in 1993. Pancrase 1 was held in Japan in September 1993, two months before UFC 1 was held in the United States in November 1993.

In 1993, the sport was reintroduced to the United States by the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC).[53] UFC promoters initially pitched the event as a real-life fighting video game tournament similar to Street Fighter and Mortal Kombat.[54] The sport gained international exposure and widespread publicity when jiu-jitsu fighter Royce Gracie won the first Ultimate Fighting Championship tournament, submitting three challengers in a total of just five minutes.[55] sparking a revolution in martial arts.[56][57]

The first Vale Tudo Japan tournaments were held in 1994 and 1995 and were both won by Rickson Gracie. Around the same time, International Vale Tudo competition started to develop through (World Vale Tudo Championship (WVC), VTJ, IVC, UVF etc.). Interest in mixed martial arts as a sport resulted in the creation of the Pride Fighting Championships (Pride) in 1997.[58]

The sport reached a new peak of popularity in North America in December 2006: a rematch between then UFC light heavyweight champion Chuck Liddell and former champion Tito Ortiz, rivaled the PPV sales of some of the biggest boxing events of all time,[59] and helped the UFC's 2006 PPV gross surpass that of any promotion in PPV history. In 2007, Zuffa LLC, the owners of the UFC MMA promotion, bought Japanese rival MMA brand Pride FC, merging the contracted fighters under one promotion.[60] Comparisons were drawn to the consolidation that occurred in other sports, such as the AFL-NFL Merger in American football.[61]

Origin of the term MMA

[edit]The first documented use of the name mixed martial arts was in a review of UFC 1 by television critic, Howard Rosenberg, in 1993.[62][63] The term gained popularity when the website, newfullcontact.com (one of the biggest websites covering the sport at the time), hosted and reprinted the article. The first use of the term by a promotion was in September 1995 by Rick Blume, president and CEO of Battlecade Extreme Fighting, just after UFC 7.[64] UFC official, Jeff Blatnick, was responsible for the Ultimate Fighting Championship officially adopting the name mixed martial arts. It was previously marketed as "Ultimate Fighting" and "No Holds Barred (NHB)", until Blatnick and John McCarthy proposed the name "MMA" at the UFC 17 rules meeting in response to increased public criticism.[65] The question as to who actually coined the name is still in debate.[66]

Regulation

[edit]

The first state-regulated MMA event was held in Biloxi, Mississippi on August 23, 1996, with the sanctioning of IFC's Mayhem in Mississippi[67] show by the Mississippi Athletic Commission under William Lyons. The rules used were an adaptation of the kickboxing rules already accepted by most state athletic commissions. These modified kickboxing rules allowed for take downs and ground fighting and did away with rounds, although they did allow for fighters to be stood up by the referee and restarted if there was no action on the ground. These rules were the first in modern MMA to define fouls, fighting surfaces and the use of the cage.

In March 1997, the Iowa Athletic Commission officially sanctioned Battlecade Extreme Fighting under a modified form of its existing rules for Shootfighting. These rules created the three 'five-minute round/one-minute break' format, and mandated shootfighting gloves, as well as weight classes for the first time. Illegal blows were listed as groin strikes, head butting, biting, eye gouging, hair pulling, striking an opponent with an elbow while the opponent is on the mat, kidney strikes, and striking the back of the head with closed fist. Holding onto the ring or cage for any reason was defined as a foul.[68][69] While there are minor differences between these and the final Unified Rules, notably regarding elbow strikes, the Iowa rules allowed mixed martial arts promoters to conduct essentially modern events legally, anywhere in the state. On March 28, 1997, Extreme Fighting 4 was held under these rules, making it the first show conducted under a version of the modern rules.[citation needed]

In April 2000, the California State Athletic Commission voted unanimously in favor of regulations that later became the foundation for the Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts. However, when the legislation was sent to the California capital in Sacramento for review, it was determined that the sport fell outside the jurisdiction of the CSAC, rendering the vote meaningless.[70]

On September 30, 2000, the New Jersey State Athletic Control Board (NJSACB) began allowing mixed martial arts promoters to conduct events in New Jersey. The first event was an IFC event titled Battleground 2000 held in Atlantic City. The intent was to allow the NJSACB to observe actual events and gather information to establish a comprehensive set of rules to regulate the sport effectively.[71]

On April 3, 2001, the NJSACB held a meeting to discuss the regulation of mixed martial arts events. This meeting attempted to unify the myriad rules and regulations which had been utilized by the different mixed martial arts organizations. At this meeting, the proposed uniform rules were agreed upon by the NJSACB, several other regulatory bodies, numerous promoters of mixed martial arts events and other interested parties in attendance. At the conclusion of the meeting, all parties in attendance were able to agree upon a uniform set of rules to govern the sport of mixed martial arts.[71]

The rules adopted by the NJSACB have become the de facto standard set of rules for professional mixed martial arts across North America. On July 30, 2009, a motion was made at the annual meeting of the Association of Boxing Commissions to adopt these rules as the "Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts". The motion passed unanimously.[72]

In November 2005, the United States Army began to sanction mixed martial arts with the first annual Army Combatives Championships held by the US Army Combatives School.[73]

Canada formally decriminalized mixed martial arts with a vote on Bill S-209 on June 5, 2013. The bill allows for provinces to have the power to create athletic commissions to regulate and sanction professional mixed martial arts bouts.[74]

MMA organizations

[edit]Promotions

[edit]Since the UFC came to prominence in mainstream media in 2006, and with their 2007 merger with Pride FC and purchases of WEC and Strikeforce, it has been the most significant MMA promotion in the world in terms of popularity, salaries, talent, and level of competition.

According to Fight Matrix, these are the promotions with the top ranked talent as of November 2024:[75]

- Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC). Based in Las Vegas, United States. Broadcasts their fights locally on ESPN (prior to 2019 on Fox Sports) and on other networks around the world.

- Professional Fighters League (PFL). Based in McLean, Virginia. Broadcasts their fights locally on ESPN and ESPN+ and streaming internationally on DAZN and other platforms

- Absolute Championship Akhmat (ACA). Based in Grozny, Russia. Broadcasts their fights on locally on Match TV, and other platforms around the world.

- Konfrontacja Sztuk Walki (KSW). Based in Warsaw Poland. Broadcasts their fights locally on the Polsat Sport 1 and other networks around the world.

- ONE Championship. Based in Kallang, Singapore. Broadcasts their fights regionally on Fox Sports Asia and streaming on their Mobile app (without Geo-blocking).

- Oktagon MMA. Based in the Czech Republic and Slovakia.

- Legacy Fighting Alliance (LFA). based in Houston, Texas. Broadcasts their fights on UFC Fight Pass.

Gyms

[edit]There are hundreds of MMA training facilities throughout the world.[76][77]

MMA gyms serve as specialized training centers where fighters develop their skills across various martial arts disciplines, such as Brazilian jiu-jitsu, wrestling, Muay Thai, and boxing. These gyms provide structured environments for athletes to prepare for competition, offering coaching, sparring, and conditioning programs. Certain gyms, such as the UFC Performance Institute offer facilities like cryotherapy chambers, underwater treadmills, and DEXA machines.[78] The following are popular MMA gyms along with notable fighters that have trained out of them.

- Jackson-Winkeljohn MMA located in Albuquerque, New Mexico – Jon Jones, Georges St-Pierre, Frank Mir, Holly Holm

- American Kickboxing Academy (AKA) located in San Jose, California. – Islam Makhachev, Khabib Nurmagomedov, Daniel Cormier, Luke Rockhold, Leon Edwards

- Serra-Longo located in Long Island, New York. – Matt Serra, Chris Weidman, Aljamain Sterling, Merab Dvalishvili

- Bangtao Muay Thai & MMA located in Phuket, Thailand. – Alexander Volkanovski, Jiří Procházka, Zhang Weili

- Nova União located in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil – José Aldo, B.J. Penn, Junior dos Santos

- Team Alpha Male located in Sacramento, California. – Urijah Faber, T.J. Dillashaw, Cody Garbrant, Gordon Ryan (grappler)

- American Top Team (ATT) located in Coconut Creek, Florida. – Arman Tsarukyan, Bo Nickal, Glover Teixeira, Movsar Evloev

- Kings MMA located in Huntington Beach, California. – Sean Strickland, Wanderlei Silva, Fabrício Werdum, Yair Rodríguez

- Blackzilians located in Boca Raton, Florida. – Rashad Evans, Anthony Johnson, Thiago Silva

- Black House (Team Nogueira) based out of Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. – Anderson Silva, Junior dos Santos, José Aldo

Fighter development

[edit]As a result of an increased number of competitors, organized training camps, information sharing, and modern kinesiology, the understanding of the effectiveness of various strategies has been greatly improved. UFC commentator Joe Rogan claimed that martial arts evolved more in the ten years following 1993 (the first UFC event) than in the preceding 700 years combined.[79]

"During his reign atop the sport in the late 1990s he was the prototype – he could strike with the best strikers; he could grapple with the best grapplers; his endurance was second to none. "

The high profile of modern MMA promotions such as UFC and Pride has fostered an accelerated development of the sport. The early 1990s saw a wide variety of traditional styles competing in the sport.[81] However, early competition saw varying levels of success among disparate styles. In the early 1990s, practitioners of grappling based styles such as Brazilian jiu-jitsu dominated competition in the United States. Practitioners of striking based arts such as boxing, kickboxing, and karate, who were unfamiliar with submission grappling, proved to be unprepared to deal with its submission techniques.[82][83][84][85][86] As competitions became more and more common, those with a base in striking arts became more competitive as they cross-trained in styles based around takedowns and submission holds.[86] Likewise, those from the varying grappling styles added striking techniques to their arsenal. This increase of cross-training resulted in fighters becoming increasingly multidimensional and well-rounded in their skill-sets.

The new hybridization of fighting styles can be seen in the technique of "ground and pound" developed by wrestling-based UFC pioneers such as Dan Severn, Don Frye and Mark Coleman. These wrestlers realized the need for the incorporation of strikes on the ground as well as on the feet, and incorporated ground striking into their grappling-based styles. Mark Coleman stated at UFC 14 that his strategy was to "Ground him and pound him", which may be the first televised use of the term.

Since the late 1990s, both strikers and grapplers have been successful at MMA, although it is rare to see any fighter who is not schooled in both striking and grappling arts reach the highest levels of competition.

Fighter ranking

[edit]MMA fighters are ranked according to their performance and outcome of their fights and level of competition they faced. The most popular and used, ranking portals are:

- Fight Matrix: Ranks up to 250–500 fighters worldwide for every possible division male and female.

- Sherdog: Ranks top 10 fighters worldwide only for current available UFC divisions. Also used by ESPN.

- SB Nation: Ranks top 14 fighters worldwide only for male divisions. Also used by USA Today.

- MMAjunkie.com: Ranks top 10 fighters worldwide for current UFC available divisions.

- UFC: Ranks top 15 contenders, UFC signed fighters only, as per UFC divisions (for example: #2 means the fighter is #3 for the UFC, behind the Champion and the #1).

- Tapology: Ranks top 10 fighters worldwide for every possible division.[87]

- Ranking MMA: Top 50 MMA World Rankings for all Men's Divisions and Top 25 MMA World Rankings for all Women's Divisions. RankingMMA publishes Independent Mixed Martial Arts rankings that does not exclude any fighter based on their promotion. RankingMMA also provides UFC Rankings (Complete Roster), Historical MMA Rankings, Non-UFC Rankings, and MMA Prospect Rankings. Ranking MMA has published MMA World Rankings since 2006.

- Sports Illustrated: Ranks top 10 fighters worldwide for current UFC available divisions.[88]

- MMA Rising: Ranks top 10 fighters worldwide in every possible division.[89] Notable for their Unified Women's Mixed Martial Arts. Rankings[90][91]

- MMA Weekly: Ranks top 10 male fighters worldwide in every possible division, and P4P for female fighters.[92] Also used by Yahoo! Sports.

Rules

[edit]

The rules for modern mixed martial arts competitions have changed significantly since the early days of vale tudo, Japanese shoot wrestling, and UFC 1, and even more from the historic style of pankration. As the knowledge of fighting techniques spread among fighters and spectators, it became clear that the original minimalist rule systems needed to be amended.[93] The main motivations for these rule changes were protection of the health of the fighters, the desire to shed the perception of "barbarism and lawlessness", and to be recognized as a legitimate sport.[citation needed]

The new rules included the introduction of weight classes; as knowledge about submissions spread, differences in weight had become a significant factor. There are nine different weight classes in the Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts. These nine weight classes include flyweight (up to 125 lb / 56.7 kg), bantamweight (up to 135 lb / 61.2 kg), featherweight (up to 145 lb / 65.8 kg), lightweight (up to 155 lb / 70.3 kg), welterweight (up to 170 lb / 77.1 kg), middleweight (up to 185 lb / 83.9 kg), light heavyweight (up to 205 lb / 93.0 kg), heavyweight (up to 265 lb / 120.2 kg), and super heavyweight with no upper weight limit.[71]

Small, open-fingered gloves were introduced to protect fists, reduce the occurrence of cuts (and stoppages due to cuts) and encourage fighters to use their hands for striking to allow more captivating matches. Gloves were first made mandatory in Japan's Shooto promotion and were later adopted by the UFC as it developed into a regulated sport. Most professional fights have the fighters wear 4 oz gloves, whereas some jurisdictions require amateurs to wear a slightly heavier 6 oz glove for more protection for the hands and wrists.

Time limits were established to avoid long fights with little action where competitors conserved their strength. Matches without time limits also complicated the airing of live events. The time limits in most professional fights are three 5 minute rounds, and championship fights are normally five 5-minute rounds. Similar motivations produced the "stand up" rule, where the referee can stand fighters up if it is perceived that both are resting on the ground or not advancing toward a dominant position.[93]

In the U.S., state athletic and boxing commissions have played a crucial role in the introduction of additional rules because they oversee MMA in a similar fashion to boxing. In Japan and most of Europe, there is no regulating authority over competitions, so these organizations have greater freedom in rule development and event structure.[citation needed]

Previously, Japan-based organization Pride Fighting Championships held an opening 10-minute round followed by two five-minute rounds. Stomps, soccer kicks and knees to the head of a grounded opponent are legal, but elbow strikes to the head are not.[94] This rule set is more predominant in the Asian-based organizations as opposed to European and American rules. More recently, Singapore-based organization ONE Championship allows soccer kicks and knees to the head of a grounded opponent as well as elbow strikes to the head, but does not allow head stomps.[95] In 2016, ONE later banned soccer kicks.[96] However, they still allow knees to the head of a grounded opponent. In 2024, the Association of Boxing Commissions and Combative Sports Mixed Martial Arts Committee made changes to the Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts, loosening the rules surrounding what a grounded opponent is, meaning fighters are now more vulnerable to kicks and knees to the head, and they also eliminated the rules prohibiting "12 to 6" elbows.[97]

Victory

[edit]

Victory in a match is normally gained either by the judges' decision after an allotted amount of time has elapsed, a stoppage by the referee (for example if a competitor cannot defend themselves intelligently) or the fight doctor (due to an injury), a submission, by a competitor's cornerman throwing in the towel, or by knockout.

Knockout (KO)

[edit]As soon as a fighter is unable to continue due to legal strikes, his opponent is declared the winner. As MMA rules allow submissions and ground and pound, the fight is stopped to prevent further injury to the fighter.

Technical knockout (TKO)

[edit]Referee stoppage: The referee may stop a match in progress if:

- a fighter becomes dominant to the point where the opponent cannot intelligently defend themselves and is taking excessive damage as a result.

- a fighter appears to be losing consciousness as he/she is being struck.

- a fighter appears to have a significant injury such as a cut or a broken bone.

Doctor stoppage/cut: The referee will call for a time out if a fighter's ability to continue is in question as a result of apparent injuries, such as a large cut. The ring doctor will inspect the fighter and stop the match if the fighter is deemed unable to continue safely, rendering the opponent the winner. However, if the match is stopped as a result of an injury from illegal actions by the opponent, either a disqualification or no contest will be issued instead.

Corner stoppage: A fighter's corner may announce defeat on the fighter's behalf by throwing in the towel during the match in progress or between rounds. This is normally done when a fighter is being beaten to the point where it is dangerous and unnecessary to continue. In some cases, the fighter may be injured.

Retirement: A fighter is so dazed or exhausted that he/she cannot physically continue fighting. Usually occurs between rounds.

Submission

[edit]A fighter may admit defeat during a match by:

- A physical tap on the opponent's body or mat/floor.

- Tapping verbally.

Technical Submission: the referee stops the match when the fighter is caught in a submission hold and is in danger of being injured. This can occur when a fighter is choked unconscious, or when a bone has been broken in a submission hold (a broken arm due to a kimura, etc.).

Decision

[edit]If the match goes the distance, then the outcome of the bout is determined by three judges. The judging criteria are organization-specific.

Technical decision: in the unified rules of MMA, if a fighter is unable to continue due to an accidental illegal technique late in the fight, a technical decision is rendered by the judges based on who is ahead on the judges' scorecards at that time. In a three-round fight, two rounds must be completed for a technical decision to be awarded and in a five-round fight, three rounds must be completed.

Other conditions

[edit]Forfeit: a fighter or their representative may forfeit a match prior to the beginning of the match, thereby losing the match.

Disqualification: a "warning" will be given when a fighter commits a foul or illegal action or does not follow the referee's instruction. Three warnings will result in a disqualification. Moreover, if a fighter is unable to continue due to a deliberate illegal technique from his opponent, the opponent will be disqualified.

No contest: in the event that both fighters commit a violation of the rules, or a fighter is unable to continue due to an injury from an accidental illegal technique, the match will be declared a "no contest", except in the case of a technical decision in the unified rules. A result can also be overturned to a no contest if the fighter that was originally victorious fails a post fight drug test for banned substances.

Clothing

[edit]Mixed martial arts promotions typically require that male fighters wear shorts in addition to being barechested, thus precluding the use of gi or fighting kimono to inhibit or assist submission holds. Male fighters are required by most athletic commissions to wear groin protectors underneath their trunks.[71] Female fighters wear short shorts and sports bras or other similarly snug-fitting tops. Both male and female fighters are required to wear a mouthguard.[71][98]

The need for flexibility in the legs combined with durability prompted the creation of various fighting shorts brands, which then spawned a range of mixed martial arts clothing and casual wear available to the public.

Fighting area

[edit]According to the Unified Rules of Mixed Martial Arts, an MMA competition or exhibition may be held in a ring or a fenced area. The fenced area can be round or have at least six sides. Cages vary: some replace the metal fencing with a net, others have a different shape from an octagon, as the term "The Octagon" is trademarked by the UFC (although the 8-sided shape itself is not trademarked).[99] The fenced area is called a cage generically, or a hexagon, an octagon or an octagon cage, depending on the shape.

-

A ring used by PRIDE

-

An octagon cage used by the UFC

Common disciplines

[edit]Most 'traditional' martial arts have a specific focus and these arts may be trained to improve in that area. Popular disciplines of each type include:[100]

- Stand-up: boxing, kickboxing, Muay Thai, karate, taekwondo, capoeira, combat sambo, savate and sanda are trained to improve stand-up striking.

- Clinch: judo, freestyle wrestling, folkstyle wrestling, Greco-Roman wrestling, catch wrestling, sanda and sambo are trained to improve clinching, takedowns and throws, while Muay Thai is trained to improve the striking aspect of the clinch.

- Ground: Brazilian jiu-jitsu, judo, sambo, folkstyle wrestling, freestyle wrestling, catch wrestling, Greco-Roman wrestling and luta livre are trained to improve ground control and position, as well as to achieve submission holds, and defend against them.

Most styles have been adapted from their traditional forms, such as boxing stances, which lack effective counters to leg kicks, the Muay Thai stance, which is poor for defending against takedowns due to its static nature and a light front leg, and judo or Brazilian jiu-jitsu techniques, which must be adapted for no-gi competition and susceptibility to strikes. It is common for a fighter to train with multiple coaches of different styles or an organized fight team to improve various aspects of their game at once. Cardiovascular conditioning, speed drills, strength training and flexibility are also important aspects of a fighter's training. Some schools advertise their styles as simply "mixed martial arts", which has become a style in itself, but the training will still often be split into different sections.

While mixed martial arts was initially practiced almost exclusively by competitive fighters, this is no longer the case. As the sport has become more mainstream and more widely taught, it has become accessible to wider range of practitioners of all ages. Proponents of this sort of training argue that it is safe for anyone, of any age, with varying levels of competitiveness and fitness.[101][102]

Brazilian jiu-jitsu

[edit]Brazilian jiu-jitsu (BJJ) is a form of submission grappling. It came to international prominence in the martial arts community in the early 1990s, when BJJ expert Royce Gracie won the first, second, and fourth Ultimate Fighting Championships, which at the time were single-elimination martial arts tournaments. Royce often fought successfully against larger opponents who practiced other styles, including boxing, wrestling, shoot-fighting, karate, and taekwondo. It has since become a staple art and key component for many MMA fighters. BJJ is largely credited for bringing widespread attention to the importance of ground fighting. BJJ is primarily a ground-based fighting style that applies close range grappling techniques and uses joint locks and chokeholds to submit the adversary. But standup techniques can also be used such as throws, holds, and strikes.

Some notable fighters who are known for using BJJ skills include: Alexandre Pantoja, Amanda Nunes, Anderson Silva, Antônio Rodrigo Nogueira, Charles Oliveira, Cris Cyborg, Deiveson Figueiredo, Demian Maia, Fabrício Werdum, Glover Teixeira, José Aldo, Junior dos Santos, Lyoto Machida, Maurício 'Shogun' Rua, Rafael dos Anjos, Ricardo Arona, Ronaldo Souza, Vitor Belfort, Wanderlei Silva, Mackenzie Dern, Aljamain Sterling, B.J. Penn, Brian Ortega, Brandon Moreno, Chael Sonnen, Demetrious Johnson, Frank Mir, Georges St-Pierre, José Alberto Quiñónez, Gerald Meerschaert, Ilia Topuria, Jan Błachowicz, Jim Miller, Nate Diaz, Gabriel Benítez, Tom Aspinall, and Tony Ferguson.

Wrestling

[edit]Wrestling (including freestyle, Greco-Roman and American folkstyle) gained tremendous respect due to its effectiveness in mixed martial arts competitions. It is widely studied by mixed martial artists as Wrestling allows competitors to control where the match will go: superior wrestlers can dominate the Clinch and take their opponents into the ground with its excellent takedowns, particularly against the legs, where they will transition into groundfighting and can either get a superior top position and start striking their opponent (a tactic known as Ground-and-Pound)[103] or start grappling for submissions. While wrestlers with stronger striking base can use defensive wrestling to defend takedowns maintain the fight in the feet where they use their superior striking, a tactic known as "Sprawl-and-Brawl",[104] or use wrestling to escape submission attempts. It is also credited for conferring an emphasis on conditioning for explosive movement and stamina, both of which are critical in competitive mixed martial arts.

There are multiple wrestling styles around the world which MMA fighters have as their base. American fighters are usually trained in folkstyle wrestling, the style competed in high school and college competitions. Many American champions were former NCAA Division I Wrestling Champions, such as Kevin Randleman and Mark Kerr. While fighters from around the world train primarily in "international" Olympic styles such as Greco-Roman and Freestyle wrestling. Some former wrestlers who competed in the Olympics have joined MMA competition, such as Daniel Cormier, Dan Henderson, Ben Askren, silver medalists Matt Lindland and Yoel Romero, and gold medalist Henry Cejudo.[105] Some fighters have also come from local Folk wrestling backgrounds, UFC flyweight champion Deiveson Figueiredo is trained at Luta Marajoara, a folk wrestling style from Marajó island.[106] Notable wrestlers who were MMA competitors include: Khabib Nurmagomedov, Jon Jones, Chael Sonnen, Johny Hendricks, Georges St-Pierre, Cain Velasquez, Chad Mendes, Randy Couture, Brock Lesnar, Mark Coleman, Frankie Edgar, Efrain Escudero, Colby Covington, Kamaru Usman, Justin Gaethje, José Alberto Quiñónez, Chris Weidman, Daniel Cormier, Dan Henderson, Alberto Del Rio, Tito Ortiz, Khamzat Chimaev, Ilia Topuria, Tyron Woodley, Yoel Romero, Deiveson Figueiredo, Mark Schultz, Anatoly Malykhin, Jason Jackson, Ryan Bader, Johnny Eblen, Daniel Zellhuber, and Henry Cejudo.

Greco-Roman

[edit]Greco-Roman wrestling is one of two styles of wrestling contested at the Olympic Games, the other being Freestyle. Greco-Roman wrestling only allows for holds above the waist and has a strong emphasis on clinch fighting. Due to the difficulty to achieve takedowns when one is not allowed to attack the legs, Greco-Roman is not utilized in MMA as often as styles that do allow fighters to attack the legs, such as Freestyle and Catch. Despite this, there have been fighters who come from a background in Greco-Roman wrestling. Notable examples are Randy Couture, Dan Henderson, Mark Madsen, Matt Lindland (all four were Olympic wrestlers or Olympic alternates), Jon Jones, Dan Severn, Ilia Topuria, Alexander Volkanovski, Magomed Ankalaev and Sergei Pavlovich.

Catch-as-catch-can

[edit]Catch wrestling is the ancestor of freestyle wrestling and includes submissions which are prohibited in freestyle wrestling.[107] Widely popular around the world during the 19th and 20th centuries, catch wrestling underwent a decline as its amateur-side became olympic freestyle wrestling, while the professional side became modern professional wrestling. Catch survived in Japanese Puroresu-style Pro Wrestling, where wrestlers such as Antonio Inoki and Karl Gotch promoted "strong style pro wrestling", that while worked, had realistic and full contact moves, resulting in the creation of the Universal Wrestling Federation and Shoot wrestling (which in their own turn would inspire the creation of legit proto-MMA shootfighting organizations such as Shooto and Pancrase). Many pro wrestlers that trained in shoot-style would later compete in MMA, which led to resurgence of Catch with the advent of mixed martial arts in the 90s. The term no holds barred was used originally to describe the wrestling method prevalent in catch wrestling tournaments during the late 19th century wherein no wrestling holds were banned from the competition, regardless of how dangerous they might be. The term was applied to mixed martial arts matches, especially at the advent of the Ultimate Fighting Championship.[108]

A lot of MMA fighters train in catch wrestling as their sole grappling style or as a complement to Brazilian jiu-jitsu, as it teaches techniques and tactics not found in Brazilian jiu-jitsu.[107] Notable MMA fighters who use catch wrestling as their primary grappling style include: Josh Barnett, Ken Shamrock, Frank Shamrock, Bas Rutten, Kazushi Sakuraba, Erik Paulson, Bobby Lashley, Minoru Suzuki, Masakatsu Funaki, Rumina Sato, Masakazu Imanari, Muhammad Mokaev and Paul Sass.[107]

Kickboxing

[edit]Kickboxing, along with boxing, are recognised as a foundation for striking in mixed martial arts, and are both widely practiced and taught. Each has different techniques. kickboxing is a group of stand-up combat martial arts based on kicking and punching. The modern style originated in Japan, developed from Karate, and had additional development in the Netherlands and the United States. Different governing bodies apply different rules, such as allowing the use of elbows, knees, clinching or throws, etc. Notable fighters include Alex Pereira, Joanna Jędrzejczyk, Zhang Weili, Edson Barboza, Darren Till, Anderson Silva, José Aldo, Charles Oliveira, Mauricio Rua, Wanderlei Silva, Ciryl Gane, Donald Cerrone, Jiří Procházka Cris Cyborg, Stephen Thompson, Mirko Cro Cop, Alistair Overeem, Israel Adesanya, Sean O'Malley, Michael Page, Yair Rodríguez, Cory Sandhagen, Alexander Volkanovski, Volkan Oezdemir, Dricus Du Plessis and Leon Edwards.

Boxing

[edit]Boxing is a combat form that is widely used in MMA and is one of the primary striking bases for many fighters.[109] Boxing punches account for the vast majority of strikes during the stand up portion of a bout and also account for the largest number of significant strikes, knock downs and KOs in MMA matches.[110] Several aspects of boxing are extremely valuable such as footwork, combinations, and defensive techniques such as slips, head movement and stance (including chin protection and keeping hands up) commonly known as the Guard position.[111] Boxing-based fighters have also been shown to throw and land a higher volume of strikes when compared with other striking bases, at a rate of 3.88 per minute with 9.64 per minute thrown (compared with Muay Thai at 3.46 and 7.50, respectively).[109] Fighters known for using boxing include: Petr Yan, Dustin Poirier, Conor McGregor, Max Holloway, Erik Pérez, Calvin Kattar, Sean Strickland, Cain Velasquez, Nick Diaz, Glover Teixeira, José Aldo, Ilia Topuria, Junior dos Santos, B.J. Penn, Dan Hardy, Shane Carwin, Jack Della Maddalena, Francis Ngannou, Alexander Gustafsson, Gabriel Benítez, Jamahal Hill, Justin Gaethje and Andrei Arlovski.

Luta Livre

[edit]Luta Livre (also referred to Luta Livre Brasileira, Submission or Esportiva) is a Brazilian submission wrestling style, developed in Brazil in the 1920s by catch wrestling practitioner Euclydes "Tatu" Hatem, including techniques from catch wrestling, judo, wrestling and Brazilian jiu-jitsu. Luta livre is divided in the categories of esportiva, which is a form of submission grappling, differentiating from no-gi BJJ with its focus on quick and energetic submissions, and vale tudo, which includes strikes both standing up and on the ground in addition to grappling and submissions.[112] Luta livre was important to the development of mixed martial arts, as rivalry between jiu-jitsu and luta livre fueled the vale tudo scene. However, the success of Brazilian jiu-jitsu over luta livre practitioners, especially after the Desafio: Jiu Jitsu vs Luta Livre event in 1991 (which was broadcast live by Rede Globo), resulted in the style waning in popularity,[113] although it seems to be making a resurgence, especially as an alternative to both Brazilian jiu-jitsu and catch wrestling.[114] Some notable luta livre practitioners in MMA include: Marco Ruas, Eugenio Tadeu, José Aldo, Renato Sobral, Pedro Rizzo, Alexandre Franca Nogueira, Terry Etim, Jesus Pinedo and Darren Till.

Judo

[edit]Judo is a Japanese grappling martial art which has both ne-waza (ground grappling) and tachi-waza (standing grappling), several judo practitioners have competed in mixed martial arts matches. They use their knowledge in judo for clinching and for doing explosive and fast takedowns which quickly transition into submission holds in the ground. However, judo is traditionally and exclusively trained using the judogi, as such, many techniques and strategies from judo can not be translated into MMA.[115] Fighters who hold a black belt in judo include Fedor Emelianenko, Marco Ruas, Khabib Nurmagomedov, Ian Garry, Dong Hyun Kim, Cub Swanson, Don Frye, Antônio Rodrigo Nogueira, Fabricio Werdum, Vitor Belfort, Benoît Saint-Denis, Merab Dvalishvili, Reinier de Ridder and Olympian judokas Ronda Rousey,[116] Hector Lombard, Rick Hawn[117] and Hidehiko Yoshida. Former WEC middleweight champion Paulo Filho has credited judo for his success in an interview.[118]

Sambo

[edit]Sambo is a Russian martial art, combat sport and self-defense system.[119] It is a mixture of judo and freestyle wrestling using a keikogi known as kurtka. Sambo focuses on throwing, takedowns, grappling, and includes submissions from judo and catch wrestling. Sports sambo is characterized as a grappling style focused in pinning and in explosive takedowns which can be quickly transitioned into devastating leglocks. Sambo also has a modality known as combat sambo, which adds punches, kicks, elbows and knees, making it a proto-MMA hybrid fighting style. Sambo is popular in Russia and eastern Europe, where it is taught as a complement to judo and wrestling training, Sambo also provides a good base for MMA with all-around skills for combining grappling and striking. Some notable Sambo fighters that transitioned into MMA include: Fedor Emelianenko, Khabib Nurmagomedov, Islam Makhachev, Igor Vovchanchyn, Oleg Taktarov, Andrei Arlovski, Yaroslav Amosov, and Shavkat Rakhmonov.

Karate

[edit]Karate is a striking-based Japanese with Okinawan origins martial art using punches, kicks, sometimes elbows, knees and even limited grappling. It is divided in various schools and styles, which distinguishes techniques, training methods, among other things. Some styles, especially Kyokushin and other full contact styles, has proven to be effective in MMA as it is one of the core foundations of kickboxing, and specializes in striking techniques.[120][121][122][123] Karate from all styles has also been a common base, with many getting introduced to martial arts and combat sports by training Karate in their youth. Various styles of karate are practiced by some MMA fighters, notably Stephen Chuck Liddell, Bas Rutten, Lyoto Machida, Stephen Thompson, John Makdessi, Uriah Hall, Erik Pérez, Ryan Jimmo, Georges St-Pierre, Kyoji Horiguchi, Giga Chikadze, Robert Whittaker, Henry Cejudo, and Louis Gaudinot. Liddell is known to have an extensive striking background in Kenpō with Fabio Martella.[124] Lyoto Machida practices Shotokan Ryu,[125] and St-Pierre practices Kyokushin.[126]

Wushu Sanda

[edit]Sanda, or Sanshou, is one of the two disciplines of sport wushu. It is a modernized and full contact version of wushu, created in the late 20th century as a condensation of traditional Chinese kung fu techniques to be used in a full contact competition environment.[127][128] It is a kickboxing style which has punching, kicking, some use of elbows and knee strikes—similar to Kickboxing or Muay Thai— but it has the distinction of allowing a range of takedowns, throws and sweeps, similar to judo and wrestling.[127][129]

They can be highly effective in competition due to their mixture of striking and takedowns, which can be easily synthesized with the rest of MMA training, such as groundfighting.[129] It is prominently used by fighters from China, but it has found a following amongst many fighters around the world.[129] Chief amongst these fighters is Cung Le, who is most notable for his TKO and KO victories over former UFC champions Frank Shamrock and Rich Franklin, and UFC strawweight champion Zhang Weili, the first Chinese champion in the UFC. Other wushu sanshou based fighters who have entered MMA include Michael Page, Song Yadong, K. J. Noons, Pat Barry, Zhang Tiequan,[130] Muslim Salihov,[131] and Zabit Magomedsharipov.[132]

Taekwondo

[edit]Taekwondo is a Korean martial art, emerging in the 1950s as a mixture between Japanese Karate, traditional Korean martial arts and some Chinese kung fu. It is a striking-based style with heavy focus on various styles of kicking, such as head-height kicks, spinning jump kicks, and fast kicking techniques.[133] Several accomplished MMA fighters have an extensive background in taekwondo, and many were introduced to martial arts through it.[134][135] Some fighters who use taekwondo techniques in MMA are former UFC lightweight champion and WEC lightweight champion Anthony Pettis, who is 3rd dan black belt as well as an instructor,[136] Benson Henderson, Yair Rodriguez, Marco Ruas and former UFC middleweight champion Anderson Silva, who is a 5th dan black belt.[137]

In his instructional book, Anderson Silva admitted the influence of taekwondo in the formation of his unique style. "In each of my fights, I tried to utilize techniques from all the various styles I had studied. I threw taekwondo kicks. I threw Muay Thai knees and elbows, and I used my knowledge of Brazilian jiu-jitsu on the ground."[138] Anthony Pettis has also stated that he is "definitely a traditional martial artist first and a mixed martial artist second",[136] as well as his "style of attacking is different [because of his] taekwondo background".[139]

Other notable fighters who have a base in Taekwondo or are known for using their Taekwondo skills while fighting include Edson Barboza, Valentina Shevchenko, Cung Le, Patrick Smith, Mirko Cro Cop, Cory Sandhagen, Israel Adesanya and Conor McGregor.

Capoeira

[edit]Capoeira is an Afro-Brazilian art form that incorporates elements of martial arts, games, music, and dance. Capoeira is often practiced as a form of dancing and game, but its origins lie as a concealed style of self-defense and combat, and can be used as such. It uses a style of fighting with quick and complex maneuvers, which use power, speed, and leverage across a wide variety of kicks, spins and techniques. Pure Capoeira is difficult to use in MMA due its complexity, but many fighters incorporated individual techniques into their reportoire.[140] Additionally, Capoeira has an importance to MMA history, as many capoeiristas participated in Vale Tudo challenges in Brazil against practitioners of other martial arts, in particular with a rivalry with Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu.[141] In 1995 at the Desafio Internacional de Vale Tudo event, Capoeirista Mestre Hulk defeated two-time BJJ world champion Amaury Bitetti using Capoeira techniques in an underdog victory.[142]

Some fighters which have trained Capoeira and incorporated techniques include Anderson Silva, Conor McGregor, Deiveson Figueiredo, Thiago Santos, Marco Ruas and Michel Pereira.

Savate

[edit]Although not as common as other disciplines, some fighters have used Savate effectively in MMA. Savate restricts the use of shins and knees, allowing only foot kicks. It focuses on kicking more than punching, and its kicks are characteristically very fast, mobile and flexible. It also possesses a complex and evasive footwork. However, because Savatuers train wearing shoes, adjustments have to be made to how they throw kicks in MMA. Notable Savate fighters include Karl Amoussou, Gerard Gordeau, Cheick Kongo, and former Bellator Light Heavyweight Champion Christian M'Pumbu.

Basic strategies

[edit]The techniques utilized in mixed martial arts competition generally fall into two categories: striking techniques (such as kicks, knees, punches and elbows) and grappling techniques (such as clinch holds, pinning holds, submission holds, sweeps, takedowns and throws).

Today, mixed martial artists must cross-train in a variety of styles to counter their opponent's strengths and remain effective in all the phases of combat.

Sprawl-and-Brawl

[edit]Sprawl-and-Brawl is a stand-up fighting tactic that consists of effective stand-up striking while avoiding ground fighting typically by using sprawls to defend against takedowns or throws.[104]

A Sprawl-and-Brawler is usually a boxer, kickboxer, or karateka who has trained in various styles of wrestling, judo, and/or sambo to avoid takedowns to keep the fight standing. This is a form which is heavily practiced in the amateur leagues.

These fighters will often study submission grappling to avoid being forced into submission should they find themselves on the ground. This style can be deceptively different from traditional kickboxing styles, since sprawl-and-brawlers must adapt their techniques to incorporate takedown and ground fighting defense. A few notable examples are Igor Vovchanchyn, Mirko Filipović, Chuck Liddell, Mark Hunt and more recently Alex Pereira, Junior dos Santos, Justin Gaethje, Andrei Arlovski,[143] and Joanna Jędrzejczyk.[144]

Ground-and-pound

[edit]Ground-and-pound is a strategy consisting of taking an opponent to the ground using a takedown or throw, obtaining a top, or dominant grappling position, and then striking the opponent repeatedly, primarily with fists, hammerfists, and elbows. Ground-and-pound is also used as a precursor to attempting submission holds.

The style is used by fighters well-versed in submission defense and skilled at takedowns. They take the fight to the ground, maintain a grappling position, and strike until their opponent submits or is knocked out. Although not a traditional style of striking, the effectiveness and reliability of ground-and-pound has made it a popular tactic. It was first demonstrated as an effective technique by Mark Coleman, then popularized by fighters such as Chael Sonnen, Glover Teixeira, Don Frye, Frank Trigg, Jon Jones, Cheick Kongo, Mark Kerr, Frank Shamrock, Tito Ortiz, Matt Hughes, Daniel Cormier, Chris Weidman, and Khabib Nurmagomedov.[103]

While most fighters use ground-and-pound statically, by way of holding their opponents down and hitting them with short strikes from the top position, a few fighters manage to utilize it dynamically by striking their opponents while changing positions, thus not allowing their opponents to settle once they take them down. Cain Velasquez is one of the most devastating ground strikers in MMA and is known for continuing to strike his opponents on the ground while transitioning between positions.[145] Fedor Emelianenko, considered among the greatest masters of ground-and-pound in MMA history, was the first to demonstrate this dynamic style of striking in transition. He was striking his opponents on the ground while passing guard, or while his opponents were attempting to recover guard.[146][147]

In the year 2000, MMA play-by-play commentator Stephen Quadros coined the popular phrase lay and pray. This refers to a situation where a wrestler or grappler keeps another fighter pinned or controlled on the mat, throwing light strikes to avoid a stand up, yet exhibit little urgency to finish the grounded opponent with a knockout or a submission for the majority or entirety of the fight, looking for a decision win through high control time.[148] The implication of "lay and pray" is that after the wrestler/grappler takes the striker down and 'lays' on them to neutralize the opponent's striking weapons, they 'prays' that the referee does not return them to the standing position. This style is considered by many fans as the most boring style of fighting and is highly criticized for intentionally creating non-action, yet it is effective. Some argue that 'lay-and-pray' is justified and that it is the responsibility of the downed fighter to be able to protect themselves from this legitimate technique.[148][149][150][151] Former UFC Welterweight champion Georges St-Pierre has been criticized by fans for playing it safe and applying the lay-and-pray tactic in his fights,[152] as has former Bellator MMA Welterweight champion Ben Askren, who justified the tactic, explaining that championship fights are much harder, as they are five rounds long compared with the usual three.[153]

Submission-seeking

[edit]Submission-seeking is a reference to the strategy of taking an opponent to the ground using a takedown or throw and then applying a submission hold, forcing the opponent to submit. While grapplers will often work to attain dominant position, some may be more comfortable fighting from other positions (ex. fighters pulling guard). It enable fighters to force opponents into submission through joint locks or chokes. Brazilian Jiu-Jitsu (BJJ) plays a significant role in MMA submission grappling, with techniques such as armbars, triangles, rear-naked chokes, guillotines, and kimuras being commonly utilized.[154]

If a grappler finds themselves unable to force a takedown, they may resort to pulling guard, whereby they voluntarily pull their opponent into a dominant position on the ground.[155] This was one of the first fighting styles that had shown success, popularized by BJJ exponent Royce Gracie during early UFC events. Submissions are an essential part of many disciplines, most notably Brazilian jiu-jitsu, catch wrestling, judo, sambo, luta livre and shoot wrestling. Submission-based styles were popularized in the early UFC events by Royce Gracie and Ken Shamrock, and were the dominant tactic in the early UFCs. Modern proponents of the submission-seeking style, such as Demian Maia, Ronaldo Souza, Charles Oliveira, Ryan Hall, Marcin Held, and Paul Craig tend to come from a Brazilian jiu-jitsu background.[156]

Clinch-fighting

[edit]Clinch-Fighting is a tactic consisting of using a clinch hold to prevent the opponent from moving away into more distant striking range, while also attempting takedowns or throws and striking the opponent using knees, stomps, elbows, and punches. The clinch is often utilized by wrestlers and judokas that have added components of the striking game (typically boxing), and Muay Thai fighters.

Ken Shamrock was known for his impressive clinch work when he submitted Dan Severn with a standing guillotine choke at UFC 6.

Wrestlers and judoka may use clinch fighting as a way to neutralize the superior striking skills of a stand-up fighter to prevent takedowns or throws by a superior ground fighter. Ronda Rousey, with her judo background, is considered a master at initiating throws from the clinch to set up armbars.[157]

The clinch or "plum" of a Muay Thai fighter is often used to improve the accuracy of knees and elbows by physically controlling the position of the opponent. Anderson Silva is well known for his devastating Muay Thai clinch. He defeated UFC middle weight champion Rich Franklin using the Muay Thai clinch and kneeing Franklin repeatedly to the body and face—breaking Franklin's nose. In their rematch Silva repeated this and won again.[158]

Other fighters may use the clinch to push their opponent against the cage or ropes, where they can effectively control their opponent's movement and restrict mobility while striking them with punches to the body or stomps also known as dirty boxing or "Wall and Maul". Randy Couture used his Greco-Roman wrestling background to popularize this style en route to six title reigns in the UFC.[159]

Score-oriented fighting

[edit]Score-oriented fighting is a style that is based around trying to win through outscoring their opponent and winning a decision. Usually fighters who adopt this strategy use takedowns only for scoring, allowing the adversary to stand up and continue the fight. They also want to land clear strikes and control the octagon. In order to win the fight by decision, all score oriented fighters have to have strong defensive techniques and avoid takedowns.[160]

In general, fighters who cannot win fights through lightning offense, or are more suited to win fights in the later rounds or via decision are commonly known as grinders. Grinders aim to shut down their opponent's game plan and chip away at them via light strikes, clinching, smothering and ground-and-pound for most of the rounds. Prominent examples of grinders are Sean Strickland, who has a very defensive and stand-up striking focused style, and Merab Dvalishvili who has a very aggressive, wrestling focused style.

Women's mixed martial arts

[edit]While mixed martial arts is primarily a male dominated sport, it does have female athletes. Female competition in Japan includes promotions such as the all-female Valkyrie, and Jewels (formerly known as Smackgirl).[161] However historically, there has been only a select few major professional mixed martial arts organizations in the United States that invite women to compete. Among those are the UFC, Strikeforce, Bellator Fighting Championships, the all female Invicta Fighting Championships, and the now defunct EliteXC.[citation needed]

There has been a growing awareness of women in mixed martial arts due to popular female fighters and personalities such as Ronda Rousey, Megumi Fujii, Miesha Tate, Cristiane Santos, Joanna Jędrzejczyk, Holly Holm, Alexa Grasso and Gina Carano among others.

History

[edit]In Japan, female competition has been documented since the mid-1990s. Influenced by female professional wrestling and kickboxing, the Smackgirl competition was formed in 2001 and became the only major all-female promotion in mixed martial arts. Other early successful Japanese female organizations included Ladies Legend Pro-Wrestling, ReMix (a predecessor to Smackgirl), U-Top Tournament, K-Grace, and AX.[citation needed]

Aside from all-female organizations, most major Japanese male dominated promotions have held select female competitions. These have included DEEP, MARS, Gladiator, HEAT, Cage Force, K-1, Sengoku, Shooto (under the name G-Shooto), and Pancrase (under the name Pancrase Athena).[citation needed]

In the United States, prior to the success of The Ultimate Fighter reality show that launched mixed martial arts into the mainstream media,[citation needed] there was no major coverage of female competitions. Some early organizations who invited women to compete included, International Fighting Championships, SuperBrawl, King of the Cage, Rage in the Cage, Ring of Combat, Bas Rutten Invitational, and HOOKnSHOOT. From the mid-2000s, more coverage came when organizations such as Strikeforce, EliteXC, Bellator Fighting Championships, and Shark Fights invited women to compete.

Outside Japan and the United States, female competition is almost exclusively found in minor local promotions. However, in Europe some major organizations have held select female competitions, including It's Showtime, Shooto Europe, Cage Warriors, and M-1 Global.

Following Zuffa's acquisition of Strikeforce in March 2011,[162][163][164][165] the UFC began promoting women's fights, with Ronda Rousey rapidly becoming one of the promotion's biggest draws.[166]

Controversy arose in 2013, when CFA (Championship Fighting Alliance) fighter Fallon Fox came out as a transgender woman. The case became a centerpiece of debates concerning whether it was fair to have a transgender woman compete against cisgender women in a contact sport.[167] Neither the UFC nor Invicta FC says they will allow her to fight, and then-UFC Bantamweight champion Ronda Rousey said she would not fight her.[168]

Amateur mixed martial arts

[edit]Amateur Mixed Martial Arts is the amateur version of the Mixed Martial Arts in which participants engage largely or entirely without remuneration. Under the International Mixed Martial Arts Federation (IMMAF) and World MMA Association (WMMAA), it is practiced within a safe and regulated environment which relies on a fair and objective scoring system and competition procedures similar to those in force in the professional Mixed Martial Arts rules.[169][170] Amateur MMA is practiced with board shorts and with approved protection gear that includes shin protectors, and amateur MMA gloves.

The International Mixed Martial Arts Federation and the World Mixed Martial Arts Association announced an amalgamation on April 11, 2018, uniting the two organizations behind one bid for Olympic sport recognition after being instructed by Global Association of International Sport Federations (GAISF). The WMMAA and the IMMAF signed a legally binding affiliation memorandum of understanding (MOU) in May 2018 and finalized the agreement by November 2018, along with the first unified world championships.[171][172]

The Global Association of Mixed Martial Arts (GAMMA) was established in 2018 by former WMMAA and IMMAF federations and representatives.[173][174] From 8 to 12 March 2024, mixed martial arts was included as a demonstration sport in the 2023 African Games in Accra, Ghana, under GAMMA.[175][176][177][178] From 11 to 13 July 2024, GAMMA member federations participated in the 2nd Asian Mixed Martial Arts Championships organised by the Asian Mixed Martial Arts Association (AMMA) under the Olympic Council of Asia.[179]

World Mixed Martial Arts Association

[edit]World Mixed Martial Arts Association (WMMAA) was founded in 2012 in Monaco by M-1 Global commercial promoters and is under the leadership of the General Secretary Alexander Endelgarth, President Finkelstein and Fedor Emelianenko.[180][181][182][183] The World MMA Association was an organization that managed and developed mixed martial arts, establishing rules and procedures, hosting MMA competitions.

On October 20, 2013, the first World MMA Championship was held in Saint Petersburg, Russia.[184]

By December 2013, WMMAA had 38 member states representing the sport and registered in accordance with national laws. By 2017, WMMAA had expanded to 83 members: Afghanistan, Albania, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Belgium, Bulgaria, Canada, Croatia, Colombia, Czech Republic, France, Guatemala, Georgia, Greece, India, Iran, Italy, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Lithuania, Macedonia, Moldova, Monaco, Mongolia, the Netherlands, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Serbia, Slovakia, South Korea, Spain, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Trinidad and Tobago, Turkey, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Venezuela.[185]

International Mixed Martial Arts Federation

[edit]On February 29, 2012, the International Mixed Martial Arts Federation (IMMAF) was set up to bring international structure, development and support to mixed martial arts worldwide.[186] IMMAF launched with support of market leader, the Ultimate Fighting Championship (UFC).[187][188] The IMMAF is a non-profit, democratic federation organized according to international federation standards to ensure that MMA as a sport is allowed the same recognition, representation and rights as all other major sports. The IMMAF is registered under Swedish law and is founded on democratic principles, as outlined in their statutes.[189] As of March 2015, there were 39 total members from 38[190] countries, which come from Austria, Bahrain, Belgium, Brazil, Bulgaria, Cameroon, Canada, Czech Republic, Denmark, El Salvador, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Greece, Iceland, India, Ireland (Northern Ireland), Italy, Jordan, Lebanon, Lithuania, Malaysia, Nepal, The Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Pakistan, Paraguay, Poland, Portugal, Romania, The Seychelles, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, Tajikistan, Ukraine, the United Kingdom, and the United States of America.[190]

The IMMAF held its first Amateur World Championships in Las Vegas, US, from June 30 to July 6, 2014.[191][192][193]

Global Association of Mixed Martial Arts (GAMMA)

[edit]